The overall goal of Pay Attention! is making racial justice real. One way we do this is by enabling people to speak their truth on the page or to the camera — people who do racial justice work and people who have experienced racial injustice.

Truth-telling and attentive listening by others to the painful truths of those wronged by racism are grounding principles in how we begin to make racial justice real.

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.”

~ Ida B. Wells

STORYTELLING

Check back for more stories — coming soon.

PERSONAL EXPERIENCES OF

RACISM IN MINNESOTA

DISCUSSIONS WITH DONALD WALKER & KENNEDY SIMPSON

DONALD WALKER

Rondo-Based Artist

Created by Antonio Richardson

Founder | Filmmaker, Nubulan Films

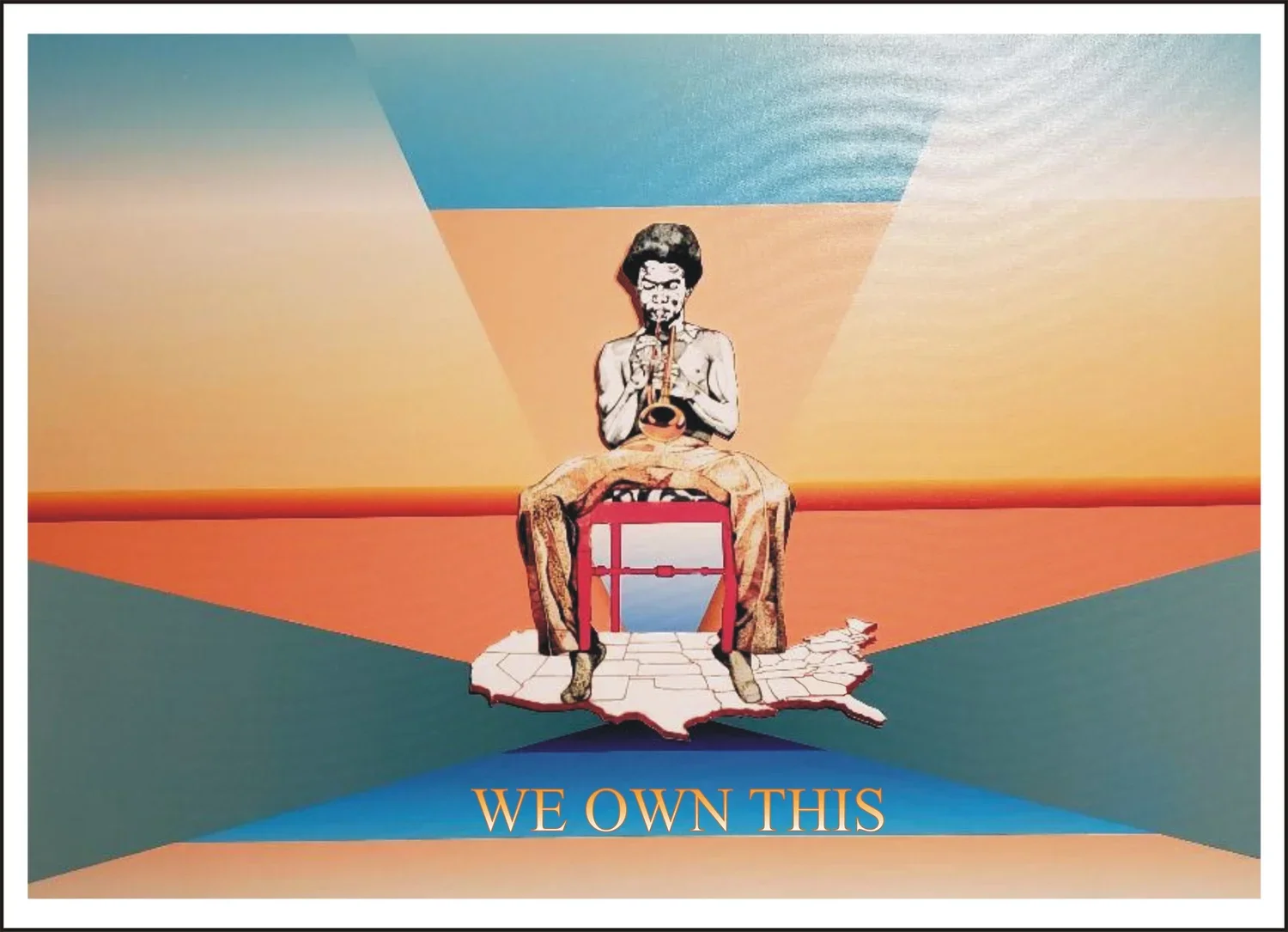

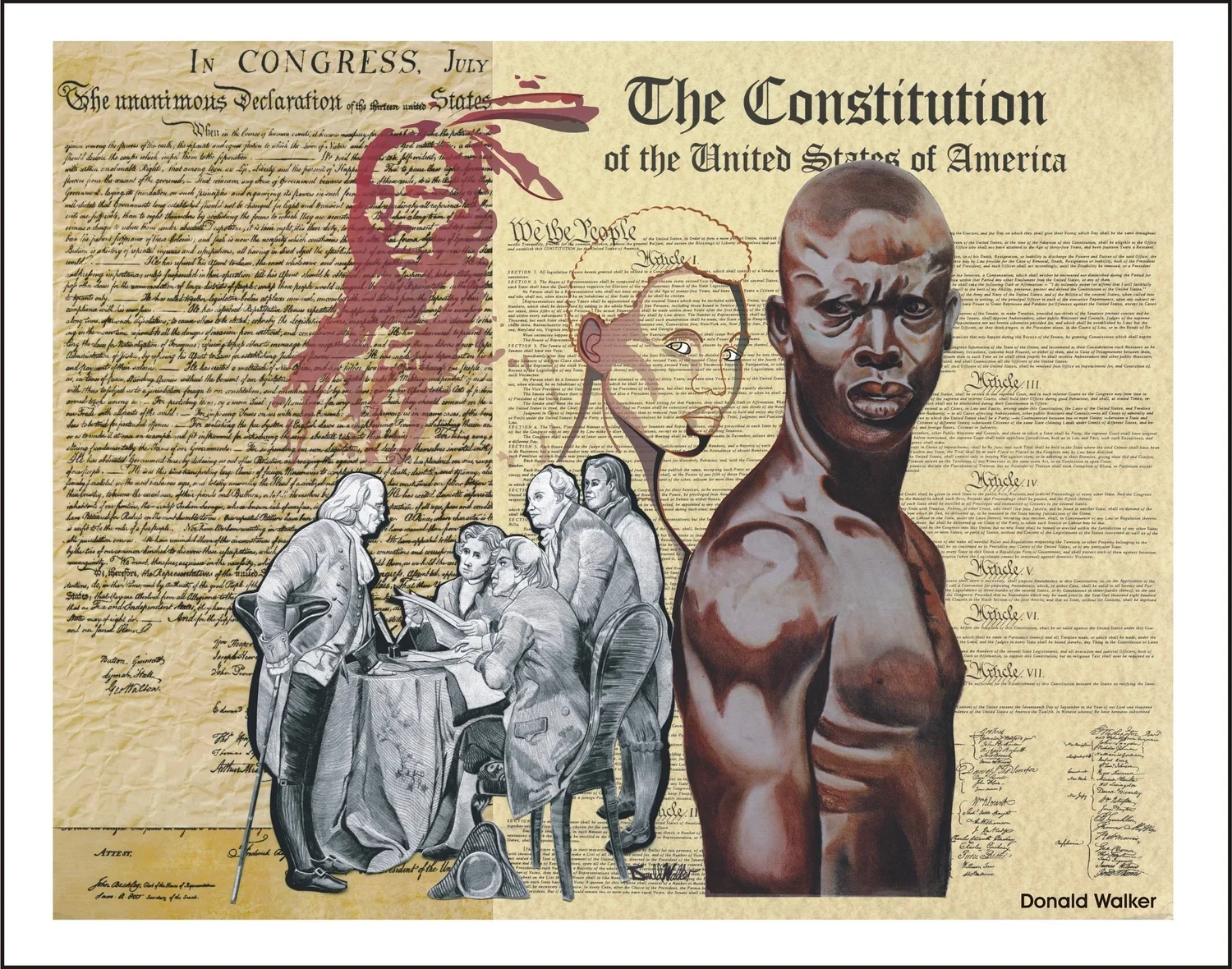

In this video, nationally-recognized Twin Cities artist Donald Walker recounts his artistic transition to becoming a social justice advocate, as he’s flanked by his eye-popping collection of posters and paintings with images of Harriet Tubman, Emmett Till, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Coretta Scott King, among many others, with their biting, truth-telling messages.

As a young cartoon artist, Donald caught the eye of his art teacher who arranged a visit to the graphics promotion department of the Pioneer Press to get pointers on his work. That group of artists was so impressed with Donald’s work — “This guy’s got skill!” — that they wanted him to intern with their team. A job interview was arranged with the Press’s publisher who acted “weirdly” upon seeing Donald, hardly saying a word to him, although a job application was filled-out. After weeks went by, finally the teacher called the Press and was told that Donald never showed up for the interview — “a straight-up racist lie,” says Donald.

Ironically, later in his career, Donald would become the first African American artist to work at the Minneapolis Star Tribune. Stinging as that early experience was, the affirmation he received from the Pioneer Press’s graphics staff for his outstanding skill — in contrast to the deceitful rejection by the publisher because of skin color — were life-lessons for Donald. An artist must be a truth-teller, front and center. “That’s how we learn, that’s how we get better, that’s what America needs to get better — the truth!”

KENNEDY SIMPSON

Kennedy Simpson Designs | Artist and Graphic Designer

Kennedy Simpson is currently a Twin Cities artist and graphic designer. In this video, she reflects back on a third-grade experience shortly after her family moved to a small Minnesota town where she was the only child of color in her school. Kennedy overheard one child say to another child, about her: “Nah, she’s not cute, she’s a nigger.” This shocking comment formed the blueprint for Kennedy's school years…feeling invisible and isolated, not smart or taken seriously. “A piece of gum on the bottom of someone else’s shoe,” she recalls. Over her school years, Kennedy wrote letters to the principal challenging the school to honor diversity and not tolerate racial slurs. Now, as an adult artist and activist, Kennedy shares her pride in that little girl who felt so small and anxious at the time.

WHY IS HARRIET TUBMAN

ON OUR HOMEPAGE?

Because symbols are powerful!

Harriet Tubman’s life and work have become a powerful symbol of resistance against oppression and a source of inspiration for movements advocating for racial justice.

Harriet Tubman is the best known “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, assisting John Brown in recruiting volunteers for his 1859 assault on Harpers Ferry, and during the Civil War for leading a Union expedition at the Combahee River in South Carolina, liberating more than 700 enslaved people. She is widely credited to be the first woman to lead an armed military operation in the United States. After the war, she relocated to Auburn, New York, where her home still stands. The Underground Railroad, as it became known, was a network of secret routes heading to Northern states and Canada, assisted by “safe houses” along the way — homes, churches, and abolitionist meeting halls. Between 1849 and 1860, Tubman made 13 trips to the South, encouraging and leading at least 70 enslaved people to follow her north to freedom.

Tubman was born into Maryland slavery about 1822. Working as a fieldhand as a teenager, she suffered a traumatic head injury as she tried to protect another enslaved person from a violent punishment; painful symptoms remained the rest of her life. In her late twenties, because Harriet feared that she and other slaves were going to be sold, she resolved to run away. In a second effort to escape, she set out alone on foot one night in 1849 with assistance from a friendly white woman who told her about the safe houses along the Underground Railroad. Traveling only at night and following the North Star, she made her way to Philadelphia where she found work. Saving her wages, Harriet returned clandestinely to the Maryland plantation the following year and again in 1851 to persuade her sister, her sister’s children, and, in subsequent trips, her brothers and their children to follow her north to freedom.

To assist in the rescue of her brother, parents, and other enslaved people, she devised clever techniques that helped make her “forays” successful. They included leaving on a Saturday night, since runaway notices couldn’t be placed in newspapers until Monday morning; appropriating a horse and buggy from the master for the first leg of the journey; turning abruptly south if she heard slave hunters’ dogs in the distance; and carrying a potion to quiet a crying child who could put the runaways in jeopardy.

Harriet was tough and determined, carrying a gun, not only for protection, but also to ‘buck-up’ her fugitives if they became tired or scared, telling them: “Be free or die.” Harriet once proudly told her friend Frederick Douglas that in all her journeys, she “never lost a single passenger.” During the Civil War, she worked for the Union as a nurse and a spy, before leading the Union raid that freed 700 enslaved people. She became known as “Moses” to her people and Frederick Douglas once said that Harriet was the “bravest person on this continent.”